What do we mean by a functional approach?

by Beverley Derewianka

In Australia, the national English Curriculum includes a Language Strand that is informed by a functional model of language. But some 15 years after it was first released, there is still some confusion over what such a model looks like.

Issues with traditional school grammar

In previous generations, students were taught ‘traditional school grammar’, focusing on the ‘parts of speech’ and how these were combined into phrases, clauses and sentences (syntax). Grammar was seen as prescriptive – setting the rules for ‘correct’ English – and was typically taught as an end in itself and out of context.

When I was in primary school many decades ago, for example, I was taught to parse endless contrived sentences by naming each ‘part of speech’, as in:

‘He was proudly telling his mother the good news about his improved reading.’

While this Latinate-based grammar provided rudimentary tools for thinking about language, researchers at the time concluded that such grammatical knowledge has little, if any, impact on students’ literacy outcomes, e.g.:

"The study of traditional school grammar (i.e., the definition of parts of speech, the parsing of sentences, etc.) has no effect on raising the quality of student writing. … Taught in certain ways, grammar and mechanics instruction has a deleterious effect on student writing. In some studies, a heavy emphasis on mechanics and usage (e.g., marking every error) resulted in significant losses in overall quality.” (Hillocks 1986)

Grammar was subsequently dropped from most school curriculums.

A functionally oriented model of language for students

In the background, however, there was a group of educational linguists who saw language not simply in terms of syntax. Rather, led by Professor Michael Halliday, they viewed language as a resource for making meaning (e.g. Halliday 1985; Martin, Christie & Rothery 1987).

They looked at how a range of genres have evolved in our culture to help us perform a variety of social purposes such as recounting what happened, explaining how something works, and arguing for a particular position. And they identified how the various genres were typically structured to achieve their purpose along with their characteristic language features.

More specifically, they explored how grammar functions in our daily lives to enable us to:

represent our experience and understanding of the world;

interact with others, take on roles and build relationships; and

create texts that are coherent and cohesive.

This functional approach to language resonated with teachers and students. It provided a way of talking about relevant choices in the context authentic curriculum tasks. It facilitated explicit discussions on how to improve students’ reading and writing.

However, in the absence of sufficient support resources, misconceptions grew. Some, for example, thought that it was a battle between ‘traditional grammar’ and ‘functional grammar’. Noticing some familiar grammatical terms such as ‘verb’ and ‘conjunction’ in the curriculum, they assumed that you could choose one or the other model, and opted for the traditional grammar that they felt comfortable with.

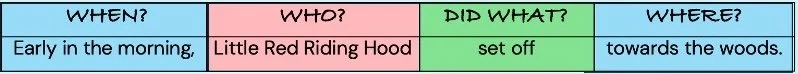

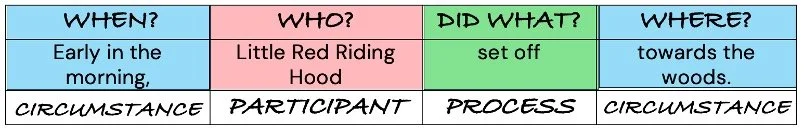

This is a misunderstanding. A functional approach looks not only at the functions that language serves but at the grammatical forms that realise those functions. We begin not by naming individual words, but by identifying ‘chunks of meaning’ in a sentence by asking probe questions such as:

Can we find the word (or group) that tells us what is happening?

Who or what are participating in this activity?

Are there any extra details surrounding the activity?

Gradually we can introduce terms that represent these three key functions:

And when it becomes useful and appropriate, we might show how these functions can take various grammatical forms:

We can even get down to the level of individual words within a group, such as when we might add describers [adjectives] to the noun group, e.g.: ‘the dark and gloomy woods’.

In summary …

A functional approach sees language as a resource for making meaning. We are interested in how learners can extend their meaning-making capacity by being explicitly taught how to make increasingly sophisticated and complex choices in the context of curriculum tasks across the learning areas.

Rather than starting with identifying and labelling the grammatical class of individual words (as in traditional grammar), a functional approach begins with an authentic sentence located in a stretch of text.

Students are taught to identify the key ‘chunks of meaning’ in the sentence by asking probe questions (and colour-coding the various elements). Gradually, terms are introduced that indicate the function of each chunk. By starting with meaning rather than abstract technical terms, we engage students with relevant accessible understandings about language.

Ultimately, we can link the functions of these chunks of meaning to their grammatical forms, bringing together function and form.

The model of language in the national curriculum is not a return to traditional grammar, but is a contemporary, meaning-oriented approach specifically designed to meet the literacy and learning needs of students from the early years through to secondary school and beyond.

Where to from here?

In future blogs, we will go beyond this very basic introduction to certain aspects of a functional approach to look in more detail at what it can offer.

References

Halliday, M.A.K. (1985) An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Hillocks, G. (1986) Research on Written Composition: New Directions for Teaching. National Council of Teachers.

Martin, J.R., Christie, F. and Rothery, J. (1987) Social processes in education, in I.Reid (ed.) The Place of Genre in Learning. Sydney: Deakin University.

About the author

Dr Beverly Derewianka is an Emeritus Professor (Language and Literacy Education) and Professiorial Fellow at the University of Wollongong, NSW.