Introducing students to the functional groupings: processes, participants and circumstances

by Brian Dare, Lexis Education

For teachers and students taking on a functional approach to learning about how language works, one of the challenges is to build an understanding of the three main components of the clause that express the content of any text. These components tell us the main happening (the process), who or what is involved in that process (the participants) and the when, where, how and why (the circumstances) linked to the process (see blog). A shorthand way of describing these options is to use the term transitivity.

Understanding the transitivity patterns of English (and any language for that matter) may look on the surface to present quite a challenge for anyone new to these functional groupings. However, I can reassure the reader that my own experience working with teachers over many years has shown that this is one of the most productive and rewarding areas of the grammar for both teachers and students. And I would add a far more efficacious way of learning about language than more traditional approaches.

As Michael Halliday points out:

‘Part of the difficulty that many children had with working on language in the old way was that learning about nouns and verbs was a classificatory exercise that had no real function or context for them, since it corresponded to nothing that they could recognize as a quest (let alone as a problem to be solved); it was a set of answers without any questions.’ (Halliday 2007: 59)

My view and that of many other teachers and students is that while it is useful at times to focus on class labels, functional groupings provide a much richer and deeper insight into how language works. By starting with clear, accessible examples as seen in the exemplars below and gradually building complexity, teachers can equip students with patterns and tools that transfer across subjects and genres, supporting their long-term academic success.

Introducing students to the transitivity

Using the following key questions is crucial for scaffolding students into a solid understanding of these fundamental components, especially in the early stages.

Figure 1

The good news is that the probe questions above not only can they be applied to every single clause in English but the frequency and intensity of the probe questions above can gradually drop away as students consolidate their understandings over time.

What text is best for explicitly teaching about transitivity?

From my own experience, I would suggest that one of the most productive ways to introduce students to transitivity is to begin with a straightforward procedural text, such as instructions for a game or a recipe or a set of rules. Procedural texts are a good choice for students at the early stages of learning about the grammar because they are typically about concrete things that you can see and touch, things students are familiar with. They also allow us to integrate the teaching of the grammatical resources as part of, and not separate from, teaching about a whole text. And of course, all undertaken as part of a rich teaching and learning cycle.

Most importantly though, as we will see from the examples that follow, using procedural texts allows us to ‘see the grammar’ more transparently. The nature of the procedure, which is commanding us to do something, provides a really useful framework to ask the key questions from Figure 1. The patterns that emerge are consistent across procedures and reflect a very genre-specific pattern in the grammar.

When is the best time to introduce our students to transitivity?

The following exemplars of teachers using this approach have been deliberately chosen to show that it is possible to introduce very young students and students who are at the very earliest stages of learning English to these central components of the clause. And I should add, my experience working with teachers is that with the right scaffolding, these practices can be applied at any stage of schooling to build students’ knowledge of how clauses and sentences work in English.

Opening up the transitivity patterns of a straightforward procedure

Let’s see how this can be done by exploring contexts from Australian classrooms, where teachers introduced students to the functional groupings for the first time.

The first context I will describe is from a New Arrivals[1] setting in Melbourne. The teacher was working with a group of students aged 10 and 11 years newly arrived in Australia with little or no English. These students were from a diverse range of language backgrounds, and some had experienced significant disruptions to their schooling, and all had no literacy competence in their first language.

After a certain time settling in and when she felt the students were ready, the teacher introduced the students to the functional groupings using a very simple procedural text[2] (see Figure 2) ‘What to do when you arrive at school’. Note how she used a much pared down and less technical metalanguage here but at the same time used the colour coding. This provided a crucial means of establishing the ‘chunks’ of meaning and made more obvious the patterns that are seen in a procedural text.

Given her students’ backgrounds, the teachers had to do a lot of preliminary work to build up their understandings of the meanings of the words we see in the text. So a lot of hands on, language accompanying action work before moving to understanding how these simple clauses work.

Adapting the questions to the classroom context

Using this modified version of the questions in Figure 1, she constructed and deconstructed versions of this simple protocol and slowly the students began to see that the (verb/process) is usually at the front, typically followed by the object involved in the process, and that the circumstances in this case are telling us ‘where’ the things are to be put. (In a procedure the ‘doer’ of the action (‘who?’) is not made explicit.)

Figure 2

After introducing students in a very gentle way as in the above example, the teacher was then able to draw on their developing understandings of the transitivity to both the comprehending and composing of simple descriptive reports on animals. From there, she and the students moved to investigating more challenging procedural texts such as the one we will now consider from Figure 3 below.

Moving towards a shared technical language

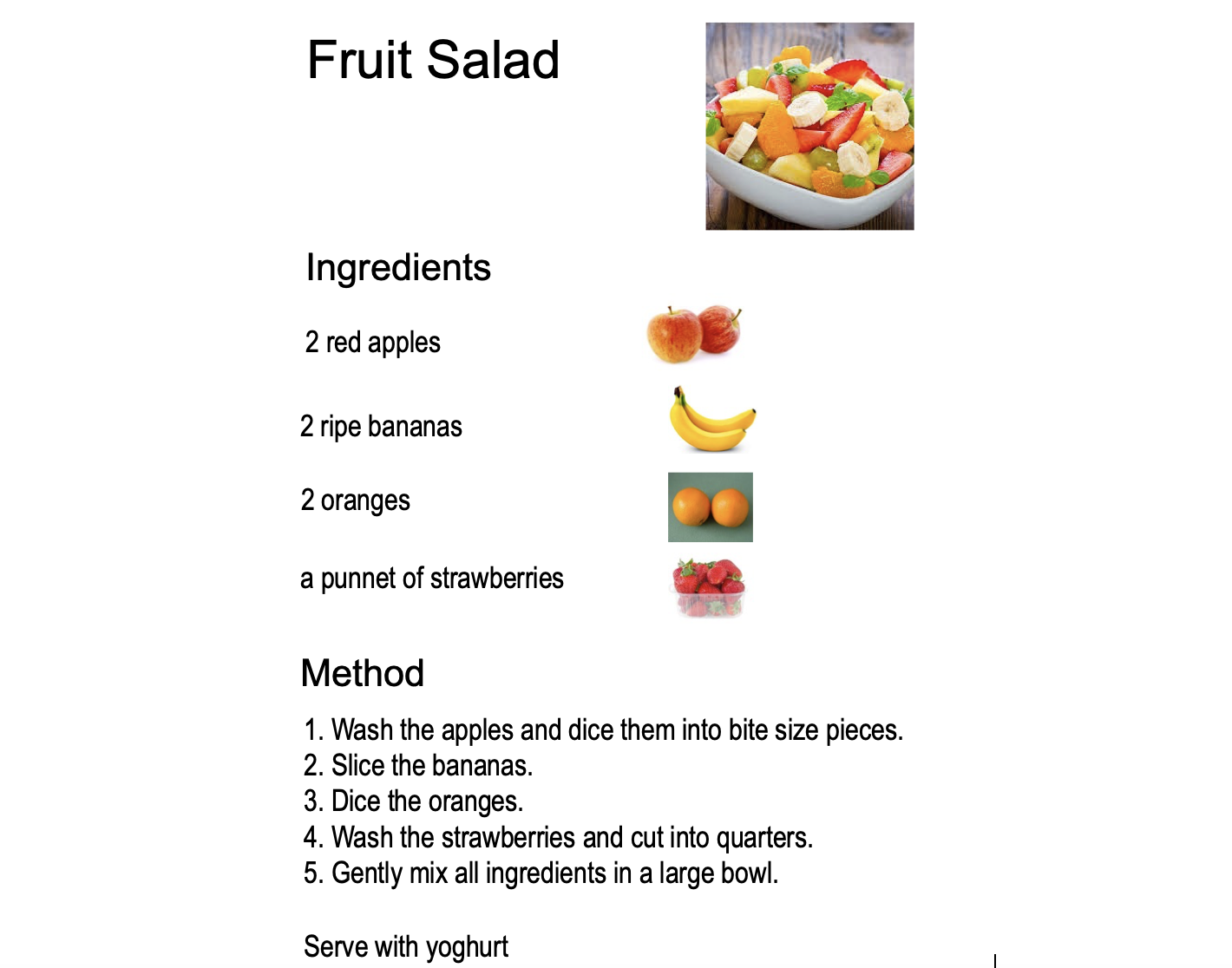

The text in Figure 3 and similar procedural texts on how to make something to eat or some object of use have been used extensively by teachers as an ideal way of introducing students to the transitivity pattern.

One of the reasons, as we said before is that such texts are very congruent with the students’ world. As such, it means that teachers and students can focus on the language structures without the stress of dealing with the meanings of a more complex field. This also allows space for building a shared metalanguage between teacher and students by introducing the technical terms for the three main components of each clause.

Figure 3

Focusing on the Method section

If we analyse the Method section for processes, participants and circumstances using the key questions as in Figure 1 and the colour coding (see blog), we end up with the following transitivity analysis:

1. Wash the apples

1a. and dice them into bite-size pieces.

2. Slice the bananas.

3. Dice the oranges.

4a Wash the strawberries

4b. and cut into pieces.

5. Gently mix all the ingredients in a large bowl.

What are the patterns that emerge?

most of the clauses begin with a process

the participants are physically close to the process and all follow the process

most of the circumstances are telling us ‘how’ with only one telling us ‘where’

only one clause begins with a circumstance

two of the clauses begin with the conjunction ‘and’

Making use of all these patterns in a unit of work

The above text has been used in several New Arrival settings where the students were at a more advanced level of English than the context described in the previous section. Here I will report on how one teacher used it to help her students build their capacity to understand how such texts worked. All the activities outlined below were carried out within an extended teaching and learning cycle undertaken over a number of lessons.

The teacher had a number of aims in mind when using this text with her class. Her broad aim was to have her students understand how procedural texts work in English. Given her students’ levels of English language, this was a major challenge. For this reason, she chose this simple recipe and made sure through all her preparatory activities and use of visuals that the students were introduced and became familiar with all the new vocabulary.

Providing high challenge with high support

This was quite a challenge for these students as they may not have seen such a text before even in their primary language and were unfamiliar with many of the words and the grammar of the method section. In using the visuals, she was able to link possibly unknown words to something the students have seen and would touch during the making of the fruit salad. In other words, using all the affordances of language accompanying action as part of the scaffolding.

Using a whole text allowed the teacher to highlight other important patterns such as the schematic structure, which moves through a number of stages: goal ^ photo of finished product ^ list of ingredients ^ method ^ coda. The teacher also highlighted the ‘command’ nature of the text with the writer taking on the role of expert instructing the reader on how to do make this fruit salad.

The text was used as a reading text, which the students then used to actually make the fruit salad.

She then analysed the method section and jointly identified the transitivity groupings with the students. This was done using the key questions shown earlier, with the students annotating their own texts using coloured markers.

Teasing out the patterns with the students

Once they had completed the analysis, the teacher then teased out with the students some of the patterns identified above. The fact that most of the clauses begin with a ‘green’ process is emphasised by the colour coding. The students pointed out that two of the clauses began with ‘and’ although they were not able to name these as conjunctions as yet.

They were quick to point out that only one clause began with the circumstance ‘gently’, which it was agreed was placed there to emphasize to the reader that the next action ‘mix’ had to be done in this manner to ensure the success of the mixing. They also identified that most of the circumstances were at the end of the clause. In later work, they were able to name these various circumstances as circumstances of manner and place.

The takeaways for the students

Now the point about this is that these patterns are very regularly repeated in such recipes so when they came to write their own recipe or read other recipes they would draw on these patterns.

While all this helped the students build their understanding of the three main grammatical components of the clause, another major takeaway for the students was that this pattern is not repeated for other genres, which have very different patterns to achieve their purpose.

What the students now had though, was a more developed understanding about how different texts work both in terms of their structures and their transitivity patterns.

These metalinguistic understandings can now be carried forward as a basis for analysing different genre in the future. I will explore this aspect in a future blog on how we might take up this knowledge about the functional groupings in a Science classroom.

In summary

I would say that there are distinct advantages in introducing students to the transitivity, even very young students and students who are very new to English. In fact, our own national curriculum states the following as an elaboration of a general capability for Level 1 students around 6 years old:

'…knowing that a single event or idea can include a process, a happening or a state (verb), the participant or who or what is involved (noun group/phrase), and the surrounding circumstances (adverb group/phrase); for example, “Teddy (participant: who or what is involved) read (process: a happening) the book (participant: who or what is involved) in the library (circumstance: where he read).’

While the new version of the curriculum does muddy the waters somewhat with its wavering metalanguage, my own experience with teachers and students has shown that a theoretically sound functional approach with its beautifully derived metalanguage provides a far superior basis for learning about language than more traditional approaches.

And there is no better place to start than building an understanding of the central components of the clause though procedural texts!

References

French, R. (2013), Teaching and Learning Functional Grammar in Junior Primary Classrooms, PhD thesis. University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

Halliday MAK (1975) Learning how to mean: Exploration in the development of language. London, Arnold.

Halliday M A K (2007) Language in Education. London, Continuum.

Halliday M A K & Matthiessen C M I M (2004) An introduction to functional grammar. (3rd ed) London, Hodder Education.

[1] All students newly arrived in Australia as migrants or refugees have the right to attend a New Arrival Language School for between 6 and 12 months to speed up their English language development before entering mainstream schools.

[2] This might also be labelled a simple protocol.

About the author

Brian Dare is an education consultant with extensive experience and expertise in the role of language in teaching and learning across the curriculum and at all levels of schooling. As a director of Lexis Education, he has co-authored a number of train-the trainer courses centred on language and literacy, all of which are underpinned by an explicit language-based pedagogy based on MAK Halliday’s functional model of language.